The latest TikTok to live rent free in my head is this, from @emilyzugay. Here’s the backstory: Emily Zugay, a creator with now over 300k followers, posts videos in which she baits trolls into hate-commenting by doing things incorrectly on purpose. In a recent post, she holds a mini golf putter backwards and swings, sending the ball directly towards an obstacle. The bait works, the misogynists expose themselves, and Emily posts a follow-up video reading the most vile comments.

In this follow-up, like in several of her prior videos, Emily is wearing wired Apple earphones, the ones that come free in the box. For a content creator, it’s as low-tech as it gets. She’s holding the left wire to pull the built-in microphone closer to her mouth. A troll, @lawdog3572, comments:

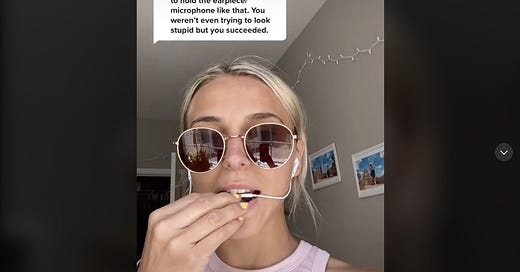

Did you know you don’t have to hold the earpiece/microphone like that. You weren’t even trying to look stupid but you succeeded.

Emily responds with a hilarious post, wearing aviator sunglasses and the same wired earphones. As she monologues, she slowly brings the mic between her teeth, then lodges it further into her mouth, distorting her voice into what commenters compare to that of a train operator, commercial flight pilot, drive-thru employee, AM radio host, and police dispatcher. She rambles, at first clearly, then nearly incomprehensibly:

Thank you for letting me know that I look stupid when I hold the microphone like this I guess I just see everybody on TikTok doing it so I thought I would participate and do the exact same but if you feel it’s dumb I [muffled] next time thank you so much thank you for commenting have a great day.

“And so I thought I would participate and do the exact same.” Participate. I’ve watched her say it over 30 times.

Stanley Milgram, the Yale social psychologist, is perhaps best remembered for his controversial experiments on social obedience, which test the ability of an ordinary person to quickly become a bona fide torture administrator when pressured by an authority figure. Like Philip Zimbardo’s 1971 Stanford prison experiment, the findings are gruesome and quite depressing. But in the 1960s, Milgram more pleasantly showed us another form of social influence: conformity.

In what’s sometimes called the “street corner experiment,” a small group of actors stood on the sidewalk, looking into the sky. As pedestrians approached, many stopped to look up as well, evidently curious about what the group was looking at. But, there was nothing in the sky to see. The pedestrians were unknowing guinea pigs, and each who stopped to look up had taken the bait.

In a 1975 film on the study, titled Conformity and Independence, Milgram says:

We are all individuals. But we live in a world with other people, and we must often accommodate to them. To what extent can we remain individuals in a social world? What kinds of pressures do others exert on us to conform? And how do we deal with such pressures?

Needless to say, these prescient questions remain ever-relevant in the digital world, some 50 years later.

There’s a thematic refrain in Mad Men that comes up in dialogue throughout the series. In S1E4, “New Amsterdam,” Roger Sterling famously tells Don Draper in one of the show’s most quoted scenes:

You don’t know how to drink, your whole generation. You drink for the wrong reasons. My generation, we drink because it’s good. Because it feels better than unbuttoning your collar. Because we deserve it. We drink because it’s what men do.

“Because it’s what men do.” We hear the refrain again in S2E2, “Flight 1." Pete Campbell has just learned that his father was on the American Airlines flight that tragically crashed in Jamaica Bay. Don attempts to console Pete, telling him to go home to be with his family. Pete, still in shock, asks why. Don responds bluntly:

Because that’s what people do.

In the 1960s, male-dominated, heavily intoxicated workplace culture of Mad Men, we see a different side to conformity, perhaps a more conservative side that is: Conformity is not just a trend; it’s a salve. A response to uncertainty. A solution to mental chaos.

There’s a line in Perks of Being a Wallflower, the film adaptation, that touches on the same refrain, for a different reason. Mr. Anderson, played by Paul Rudd, asks a question to his class. Charlie, played by Logan Lerman, writes the answer in his notebook, but doesn’t raise his hand. Mr. Anderson sees this, and tells Charlie after class:

You should learn to participate.

Here we see conformity not in opposition to individualism, but instead to introversion. This, it seems, is key for me: individualism, linked to introversion, at odds with participation.

In college, I sidelined myself from drinking games when all I had to do was grab a ping pong ball and join in. At professional conferences, I stuffed my lanyard into my backpack, when everyone else wore theirs. And when George Floyd was murdered, I chose not to post a black square on my Instagram.

The thing is, I could stand on my soapbox and justify these decisions. I could tell you all of my thoughts on fraternity drinking culture, exclusive networking events, and performative activism. I could tell you I exercised individual thought, and made independent choices.

What I see now, more clearly, are all of the ways that I failed to participate. I see now that participation can be a salve. I see now that there’s so much to gain from just playing along. Being a part of something. Signaling support for the cause. And so I’m learning to recognize when to let my independent thoughts take a back seat, and just do what people do.

So, lately, I’ve been leaning into that feeling, even when I’m alone. In November, I spent Thanksgiving solo due to the pandemic. My roommates chose to travel, my sister stayed in Chicago, and my parents were at home in Pennsylvania. All alone, I asked myself, should I even do Thanksgiving? What’s the point of eating stuffing? The answer: Yes, because that’s what people do. And so I did. By myself, in my apartment, participating for the sake of participating.